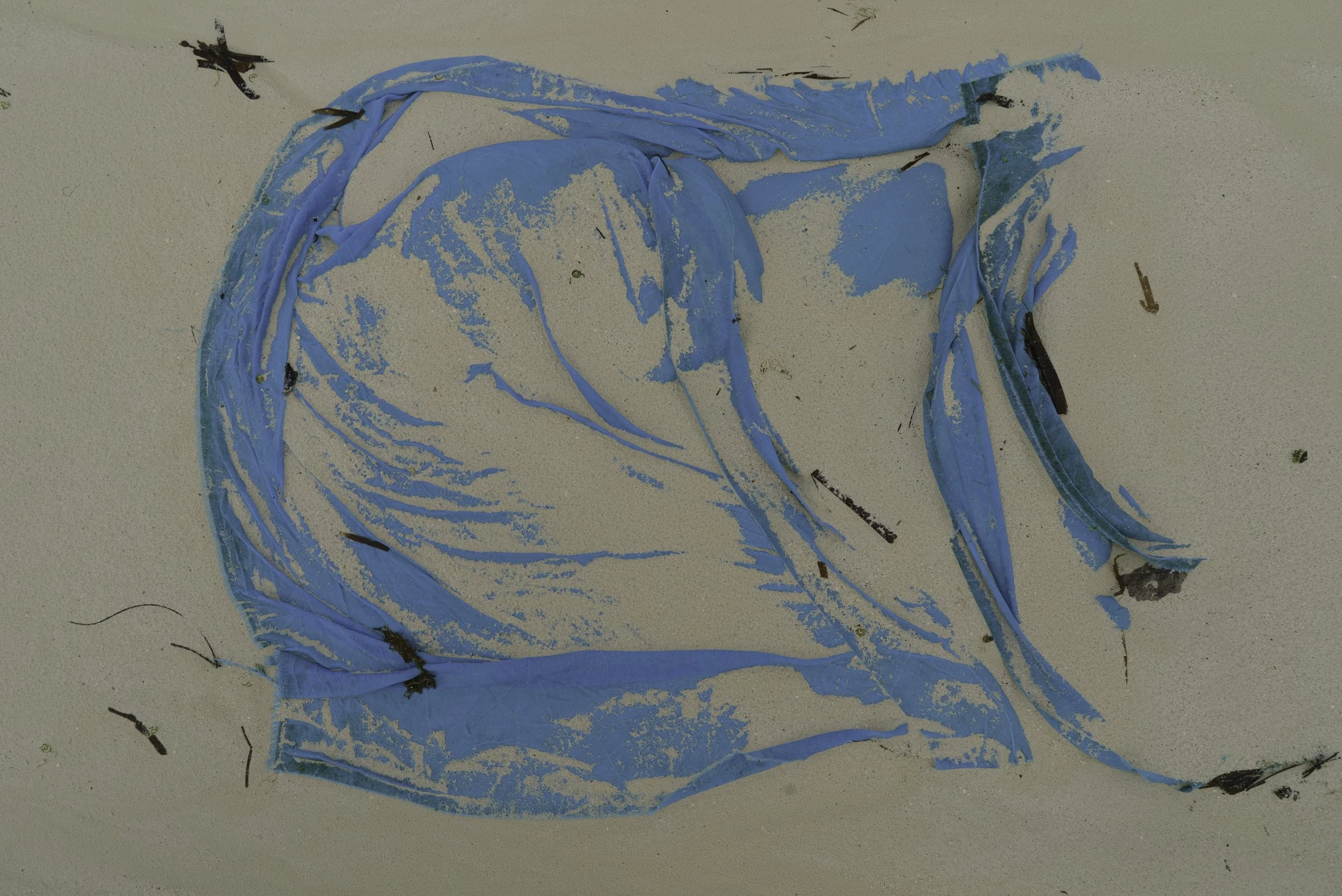

SEA RAGS

I found them scattered along the Zanzibari shore — colorful kangas, half-buried in sand, faded by sun and sea. Once wrapped around living bodies, they now lie quietly at the water’s edge. No one comes to claim them.

The kanga is more than cloth. It is language, identity, memory. For generations, women have used it to speak — through its colors, its patterns, its printed words. It has wrapped bodies in joy and in grief, witnessed births, unions, prayers, and sometimes farewells. Its messages are often whispered rather than shouted, carrying fragments of personal and collective histories across the Swahili coast.

Here, those voices have fallen silent. Some of these fabrics may have been left behind after funerary rituals, set at the ocean’s edge as offerings. Others may have drifted, torn loose from their original places. Their exact stories are lost, but what remains is their presence — traces of the East African women who once wore them with pride.

The shoreline is a threshold. Neither land nor sea, neither home nor away. This is where the kangas rest, caught in the in-between. Their fading patterns and vanishing words echo how displacement lingers: quietly, stubbornly, long after movement or loss.

In these half-buried cloths, I see the layered dimensions of displacement: physical, cultural, emotional. Bodies that once inhabited these garments have moved on — through migration, through death, through the slow erasure of time. Their fabric remains, stripped of voice, yet still speaking of departure and what endures after.

This series listens to what is left behind. Each kanga is both remnant and witness, a silent proxy for a life, a ritual, a story. In their stillness, they reflect the universal human experience of leaving and being left — how displacement does not only move people, but also their words, their identities, their traces.